Guest post by Daniel Morrow

Sensationalism in some of the tabloid press in the UK is hardly a recent phenomenon, with much of their reputation built on vilifying marginalised groups in a bid to pander to right wing ideology. But, in the face of what has been described as an “uncontained HIV outbreak” in Glasgow, the potentially damaging language used by the media in Scotland to describe so-called ‘junkies’ must be held to account.

To put the crisis into context: in 2017, there was a reported 26% increase in new cases of HIV, with each of these cases being attributed to problem users of heroin. It’s estimated that one in five people who inject drugs in public places are now infected with HIV. Health Protection Scotland has claimed that it is the worst seen in the UK for decades, with the rate of new cases of the virus reportedly trebling in the past two years.

“The outbreak affects some of the most marginalised people in society” says David Liddell, CEO of the Scottish Drugs Forum. “They live in poverty, many are affected by homelessness and around the city centre suffer verbal and other abuse.”

Glasgow-based medical experts have recommended a radical option to remedy the crisis with a Safer Drug Consumption Facility (SDCF) – a clinic where users are provided with a room to inject, equipped with clean needles, in addition to access to anti-overdose treatment supplied by medical professionals who also safely dispose of used needles.

These types of clinics have been in operation around the world since 1986, when the first supervised facility opened in Berne, Switzerland. Often these facilities were opened as a reaction to health and public order concerns linked with the consumption of drugs. Some of these clinics were seen as experimental, coming under stiff opposition.

Those suffering as a result of problem drug use register with the clinic, where they are allowed to bring in their own drugs without the fear of being reprimanded by the authorities. Other facilities supplied include the provision of food, showers and access to clothing for those who are currently living on the streets. Clients also receive counselling, drug treatment and regular HIV tests.

There is compelling evidence to support that these facilities have been of great benefit to the cities where they have been implemented. In 2010, a study conducted at the Insite clinic in Vancouver, Canada said that it had prevented 35 new cases of HIV and saved almost three lives per year. An earlier study on the clinic in 2007 surveyed 100 clients with a majority claiming that they were more careful about syringe disposal.

One clinic in Barcelona, which opened in 2004, led to an unprecedented reduction in the number of unsafely disposed syringes being collected in the city, from 13,000 recorded in 2005 to 3,000 in 2012.

“Safer Drug Consumption Rooms are something that can be quite a positive and can change people’s mindsets of how we address drugs in society”, says Paul Sweeney, Labour MP for Glasgow North East. Sweeney was one of 36 Scottish MPs that signed a cross-party letter in January this year. The letter was addressed to then Home Secretary Amber Rudd and demanded action from the Home Office to bring changes to drug laws to allow the green light to be given to a Safer Drug Consumption Room (SCDF) in Glasgow.

The plans have been approved by the Scottish Government and the Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership, but the proposals have since been quashed by the Home Office, with the UK Government having the final say on any amendment to the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act.

In April this year, a Home Office spokesperson said: “The UK’s approach on drugs remains clear – we must prevent drug use in our communities and support people dependent on drugs through treatment and recovery.”

Just months prior to this statement, in September last year, Scotland’s busiest needle exchange – in Glasgow Central Station – was closed by Network Rail. The facility had opened in July 2016 due to a spike in the number of HIV cases in the city. Network Rail said they were forced to take this action after drug taking equipment was found in public areas.

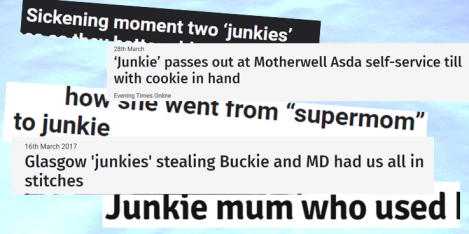

Both of these setbacks can be attributed, in part, to the portrayals that are pushed by some of the tabloid press in Scotland. Their particular fixation with the term ‘junkie’ to describe those who have fallen into an addiction to drugs are there in plain sight within the headlines of some articles.

Some recent examples include the “the shocking moment a so-called “junkie” passed out at an Asda self-service checkout with a cookie in hand” from the Evening Times, the Daily Record reporting on a “junkie jailed” and a Dundee murder victim who “went from ‘supermom’ to junkie” in the Scottish Sun.

“Some papers like to moralise”, says David Liddell, who has been largely in favour of the radical proposals to have a SDCF in place in Glasgow’s City Centre. “It suggests that people are morally weak or defective or have made lifestyle choices. But it is so far from the lived experience of someone physically or psychologically dependent on drugs. Demonising people gives no insight to their readers, it simply allows them to judge and dismiss people.”

The Global Commission on Drug Policy had stated in a report published earlier this year that there is evidence to suggest that problem drug users are already given little help with accommodation. Furthermore, they have evidence to state that two-thirds of employers would never employ someone who previously had an addiction to heroin or crack cocaine.

In their report, they cited research where they found that a problem drug user was less likely to be given adequate treatment if they were referred to as a “substance abuser” compared to referring to them as “someone with a substance abuse disorder.”

“I think continuing to refer to people in this way is incredibly disruptive”, says Paul Sweeney. “It’s exactly why the Tory Government is not willing to face up to the evidence of why SDCFs are actually a positive when helping to improve public health. They are not willing to help because they are willing to pander to right-wing framing of how drug addicts fit into society; it is about pouring scorn onto them, it’s about casting them out and treating them as some sort of lepers. It’s a Victorian attitude that we really need to challenge.”

The World Health Organisation has previously described drug dependence as “A complex disorder with biological mechanisms affecting the brain and its capacity to control substance use. It is not only determined by biological and genetic factors but psychological, social, cultural and environmental factors as well. Currently there are no means of identifying those who will become dependent either before or after they start using drugs. Substance dependence is not a failure of will or of strength of character but a medical disorder that could affect any human being. Dependence is a chronic and relapsing disorder, often co-occurring with other physical factors and mental conditions.”

Currently, there is no specific reference in the Editors’ Code – policed by IPSO – that concerns stigmatising drug users, where words such as ‘junkie’, ‘drug abuser’ or ‘crackhead’ have been perceived as defining people as ‘the other’ or as morally flawed individuals.

However, moves are being made in ridding journalism of this type of damaging language. The Associated Press Stylebook of 2017 advises to avoid the use of words such as “addict”, “abuser” or “alcoholic” and called for journalists to replace them with “people who have an addiction” or “people who use drugs”.

It is evident that this has failed to filter through to the Scottish media, who continue to demonise and stigmatise problem drug users. This is despite clear evidence to suggest that this negative stereotyping has a problematic affect in a recovering user of drugs’ pursuit of basic essentials such as housing and stable work, in addition to adequate care as a means to breaking this tragic and vicious cycle of destitution.

The current HIV outbreak in Glasgow now enters into its third year, and its pertinent that journalists have a rethink in their language if they want to make a serious contribution in alleviating a crisis that shows no signs of ceasing.

@dnlmrrw

————————————————————

Further reading:

We Have to Turn the Tide on Scotland’s Rising Drugs Deaths

Drugs & The Scottish Government – Ask the experts, Just say no anyway

Methadone isn’t the problem or the only solution

If taking pills is Russian roulette, we need to make the odds better

————————————————————

Find us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/AThousandFlowers

Follow us on Twitter @unsavourycabal

————————————————————

In terms of HIV we have had clear reporting guidelines for less stigmatising language. Each and ever time I see the terms “Aids victims” or “Suffering from HIV” I make a point of writing to the editor and the journalist pointing out the code and demanding a correction. It can be a quick and simple behaviour change intervention with longer term benefits if it is pitched to them in a certain way.

I have mixed feelings about this article. Drugs do cause massive problems in our society, and people under their influence are responsible for a level of crime and vandalism which is not acceptable. I’m well aware that many decent folk end up becoming addicts, but painting this phenomenon in politically correct terms? Just no…